No Longer Lost, a Refugee Accepts Call to Leadership

By NEELA BANERJEE

Aug 19, 2007, The New York Times

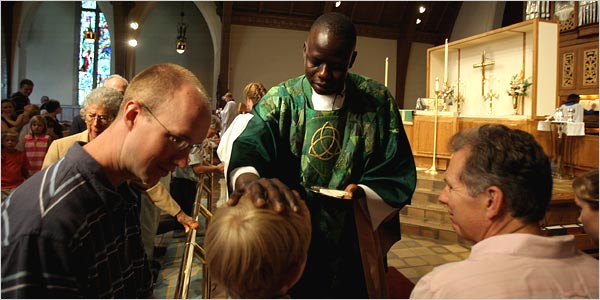

Fabrizio Costantini for The New York Times

| |

In Grand Rapids, Mich., the Rev. Zachariah Jok Char serves an Episcopal congregation that welcomed Sudanese refugees. |

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. — About 7,000 miles separate Grace Episcopal Church here, where the Rev. Zachariah Jok Char preaches most Sundays, from the small town of Duk Padiet in Sudan, where he was born.

The tally of the miles started about 21 years ago when Mr. Char was 5 and militias backed by the Sudanese government attacked his town during the civil war in the south. He saw the explosions from the field where he was playing, and he fled. He met other boys who had escaped similar attacks, and they started walking.

“I still remember what I was wearing then: red shorts and a T-shirt,” said Mr. Char, sitting in an empty pew one afternoon at the church. “I didn’t have shoes. Some were naked.”

The orphans, mostly boys, walked more than 1,000 miles to Ethiopia from Sudan over three months, Mr. Char said. Later, they were forced to walk to Kenya. Thousands died. The West called them the Lost Boys.

Those boys are men now, and here and in cities like Atlanta and Burlington, Vt., the 3,800 who were resettled in the United States beginning in 2001 are trying to build lives and weave communities. For many, their Christian faith, often Anglicanism, is at the heart of their efforts.

Even as they struggle with school, work and frequent bad news from home, recent Sudanese immigrants have moved rapidly to establish congregations, often with the help of local Episcopal parishes. For the Sudanese, church is a place where they can be themselves after being Americans all week, where they can hear Scripture in their native language and where they can reconstitute a culture they only began to know as children.

“We want to pray God, God who brought us here,” Mr. Char, 26, said of the formation of the congregation at Grace Episcopal. “It was not a human decision but a God decision that we are here.”

The Sudanese want their own to lead them. So at a ceremony on June 16, the bishop and clergy members of western Michigan laid their hands upon Mr. Char and welcomed him as a priest in the Episcopal Church, among the first of the Lost Boys to be ordained.

Mr. Char has taken on a burden, as he ministers to his people while attending college and working at a meat-processing plant, both full time. His work as a priest makes it possible for the Sudanese church members to receive communion and have their baptisms, weddings and funerals in Dinka, their language.

Occupying a block in the city’s most affluent neighborhood, Grace Episcopal was former President Gerald Ford’s place of worship. As coffee hour for an English-language service ended one Sunday, the drums, shakers and a cappella singing of the 11:30 Dinka service filtered into the churchyard.

There is no program for the service, no organ music. Hymnals and prayer books in Dinka are in the first several rows of the large sanctuary. Songs rise from one or two people and are taken up by everyone else. Yet those familiar with the Anglican liturgy could follow the service and might recognize, even in Dinka, the solemnity of the Lord’s Prayer.

“It’s very powerful, very meaningful to come together and worship in your mother tongue,” said Mayen Wol, 42, a leader in the congregation who came to the United States years before the Lost Boys. “We have common problems: your brother was killed yesterday, your sister raped, your father killed. Through gathering, we encourage each other, through prayer.”

The arrival of the Sudanese immigrants at Grace Episcopal four years ago has changed the way some other congregants understand faith.

“I don’t know how a 5-year-old could have walked across a burning desert: there is something biblical to it,” Nancy Tweddale, a junior warden at the church, said of Mr. Char. “He remembered what he heard in Sunday school, that God was with him. If I saw my friends falling and dying around me, or being killed by animals, I would wonder if I weren’t very alone.”

The war in southern Sudan lasted more than 40 years, killing an estimated 2 million people and displacing millions of others. In 2005, the government in Khartoum and the leaders of rebel movements in the south agreed to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which has proven tenuous.

About 28 Sudanese Episcopal congregations dot the United States. Though priests ordained in Sudan have worked in this country before, some new Sudanese congregations are offering their own members, usually lay pastors, for ordination.

“This was done by Irish and Italian immigrants in the Roman Catholic Church,” said the Rev. Richard Jones, president of the American Friends of the Episcopal Church of Sudan. “The legitimacy comes from being a leader recognized according to the traditional marks of leadership in a community and from meeting the norms of the host church.”

The Sudanese immigrants in Grand Rapids chose Mr. Char for ordination just as they came together as a congregation. Grace Episcopal was the host of the visit of the Anglican primate for Sudan in 2003, and the church then offered itself as a new home to the immigrants gathered to greet the church leader.

The Sudanese congregation has taken root here at a time when many Anglican leaders in Africa have harshly criticized the Episcopal Church in America for its consecration of an openly gay bishop. The church in Sudan has not rejected the American church, however. In Grand Rapids, the Sudanese church members said they are conservative about sexuality but feel no pressure from the Americans to change their views.

Mr. Char had been active at a refugee camp in Kenya as a lay pastor, leading a congregation of 1,000. His embrace of preaching came after he nearly turned away from God, he said.

“I had not seen my parents in 12 years,” Mr. Char said. “I did not know where was God.”

“I felt God brought me to the world and didn’t take care of me,” he continued. “Then in the eighth grade I read the Book of Ecclesiastes, and there was a time for everything: a time when I was with my parents, a time for suffering, and a time when I would have hope again.”

Mr. Char took correspondence classes from the Trinity Episcopal School for Ministry in Pennsylvania to prepare for ordination, all the while attending college and working, most recently at a meat processing plant. He gets no salary as the rector of the Sudanese congregation. Recently naturalized, Mr. Char also supports his wife and infant son in Kenya, and he is trying to bring them here.

Mr. Char said he gets tired. But like many other Sudanese church members, he said he survived for a reason, that it was not just luck. It might be to rebuild southern Sudan some day, the immigrants said, or to serve their people here now.

“It is a heavy job,” Mr. Char said of his jam-packed life. “But in Sunday school, we were told when you are a kind person, God will give you a long life. The only way people can stay kind is hearing the word of God every day and staying involved in the community.”

|