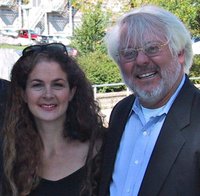

The fact that Time magazine named Zeng Jinyan, right, one of the world's 100 most influential people did not help her much on Dec. 27, when 30 Chinese agents arrested her husband, prominent rights activist Hu Jia.

Security agents showed up at the couple's Beijing apartment with a warrant for "subversion against the state," a catch-all phrase used to lock up pretty much anyone who says something the Communist Party does not like. Despite liver problems and a two-month-old daughter, Hu now potentially faces years in prison.

He is not alone. Three months ago, one of his best friends -- leading rights attorney Gao Zhisheng -- met a similar fate. On Sept. 22, Gao, who like Hu had recently questioned the legitimacy of Beijing hosting the Olympic Games, was apparently taken by plainclothes police from the home he shares with his wife and two children. He has not been seen since.

To those who follow human rights in China, these may seem like common scenarios. But these two men are anything but common -- they are key leaders of what is often termed China's Rights Defence Movement, a diverse collection of lawyers, intellectuals and activists. Reaching beyond a narrow elite of dissidents, they have drawn support from large numbers of farmers and workers as they use nonviolent means to demand basic rights and challenge the Communist Party's decades of repression.

Hu and Gao's work has focused on different issues. Hu is an environmental and AIDS activist, while Gao has represented the gamut of China's "have-nots," from disabled children to coal miners to evicted tenants. As a Christian, he is particularly passionate about defending victims of religious persecution, especially house-church members and people who practise Falun Gong.

The duo's approach for bringing change has been surprisingly bold. Besides publicly quitting the Communist Party, in February, 2006, they launched a relay hunger strike for human rights which quickly became one of the largest and most unified mobilizations in years.

Activists, farmers and workers from 29 provinces joined, as well as overseas democracy activists. Gao has received phone calls of support from sympathetic government officials. In

regular touch with activists and petitioners across the country, Hu Jia has acted as a funnel, channelling to the rest of the world how people on the ground in China actually feel.

No wonder the Communist Party fears them.

As the Olympics approach, there is a prevalent sense that the world is in for a spectacular display of anti-Communist Party demonstrations, potentially met by violent repression. Here in the West, this is often accompanied by an implied attitude of "let's watch and see what happens," as if we were not a party to this battle.

But we already are, certainly when these rights defenders are getting in trouble precisely for asking our help. Gao was detained in September within days of sending a letter to U.S. Congress stating the Olympics are hurting the Chinese people and should be boycotted. Hu Jia expressed similar sentiments last month when he testified via webcam at a European Parliament briefing on China.

Despite what our leaders may say, public international pressure makes a difference. It is what kept Hu and Gao out of jail for as long as they were. It is also what turned Gao's three-year prison term in 2006 into a "suspended sentence," which at least protected him from torture.

But the dynamic works both ways. With every arrest, Party leaders watch to see how the world will react. When there's silence, when Western states continue to dutifully roll out the red carpet for every Chinese delegation, when abuses barely get mentioned at press conferences, then Chinese security agencies step up arrests. That is exactly what we have seen happen for the past year and a half.

And it is already playing out in Hu's case. With no outcry from the International Olympic Committee or Western governments since his detention, his lawyers are now blocked from visiting him, placing him at greater risk of torture.

That is why the international community cannot stand on the sidelines. Silence is a stance in itself--a stance on the side of the authoritarian Communist

Party's regime. And if Hu and Gao's work shows anything, it is that this is not the side that tens of millions of Chinese people really want us on.

cook@freedomhouse.org. - Sarah Cook is a research assistant at Freedom House and co-editor of the English translation of Gao Zhisheng's memoir, A China More Just.